Here is a 2025 up-to-date guide to Machu Picchu, where people from all over the world venture for a shared dose of awe and awakening. This comprehensive guide covers everything from Machu Picchu circuits and maps to tours, tickets, and essential visitor information.

No photograph or description can capture the experience. You must be there for that moment when you first set eyes on the monumental Inca architecture perfectly perched between two craggy mountain peaks. Now read this Machu Picchu guide for 2025.

The Machu Picchu Sanctuary is located 45 miles (73 km) from the Plaza de Armas of Cusco, Peru, South America. The nearest population center — and main gateway to the ancient citadel — is the town of MachuPicchu Pueblo, more commonly known as Aguas Calientes. There is no direct road access to this small bustling town, so the only way to get to it is by train or on foot. The main entrance to Machu Picchu stands at an elevation of 8,000 feet (2,438 meters) above sea level, on the mountaintop above Aguas Calientes.

Given its location within the Peruvian Andes, it makes for an ideal stop when visiting nearby Cusco. There are several different ways of traveling through the mountains to reach Machu Picchu, such as hiking the Inca Trail or traveling by luxury train. Here at Fertur we offer both options with our various Peru Package Tours, which are customized for you depending on your own interests and travel tastes.

To get up to the sanctuary, you can choose between a 75-minute to 2-hour hike (how long depends on your fitness) or boarding one of the buses that depart from Aguas Calientes every five minutes between 5:30 a.m. and 3:30 p.m. The buses take about 25 minutes to ascend the switchback Hiram Bingham road. Tickets for the bus are sold adjacent to where the vehicles depart, but there are often long lines. Also, Machu Picchu tickets are NOT sold at the entrance gate above.

There is a Ministry of Culture office just off the main square in Aguas Calientes (Machupicchu Pueblo) where a limited number of entry tickets can be purchased one day in advance between 3:30 p.m. and 10:00 p.m. You can go online to reserve these tickets 48 hours ahead of time, subject to availability.

But buying them this way, last-minute, is not advisable. Tickets can sell out days — or during the busiest season (June through August) weeks — ahead of time. So it is a good idea to buy both the bus ticket up to the sanctuary and entry ticket into the citadel well in advance. Visitors can also check availability and purchase tickets on Machu Picchu’s official website.

The updated entry times for Machu Picchu in 2025 are structured to streamline and efficiently manage visitor flow to minimize the impact of foot traffic. The site is open daily from 6:00 AM to 5:00 PM, with specific entry slots available each hour until the 3 p.m. hourly period.

Each entry ticket has a 1-hour window for entry, and there is a 45-minute tolerance period for entering the main gate.

The maximum number of visitors per day is 4,500 during the low season and 5,600 during the high season (June 1 to October 15).

One thousand of those tickets are available for sale daily, in person in Machupicchu Pueblo (Aguas Calientes), the town below Machu Picchu. They are sold on a first-come-first-serve basis and can only be purchased one day in advance of entry. However, we highly recommend that you purchase your tickets well in advance of your trip.

Visitors must be accompanied by a certified guide*, either in private or in small groups, to enter the sanctuary and tour one of four established routes. In addition, visitors can choose ahead of time to purchase entry tickets to climb Machu Picchu Mountain, Huchuypicchu Mountain or the iconic peak of Huayna Picchu.

*Note: The rule requiring visitors be accompanied by a certified guide is strictly enforced for groups. The regulation, however, is currently not enforced in practice for individual tourists. Visitors can tour the Inca Citadel without a guide, although one is highly recommended.

Overall Machu Picchu is a safe site to visit, as long as you follow the rules which are there to help keep tourists safe. This includes following the marked signs, as well as not passing the ropes. There are lots of stone steps that you will need to walk up and down, so it’s worth bringing comfortable shoes that have good grip (especially if coming in the wet season). If you are bringing children to Machu Picchu, then it’s important to keep them close given what we mentioned above, and also as the site is quite big. It’s also worth taking frequent breaks to rest, which are best done at the different viewpoints when taking photos.

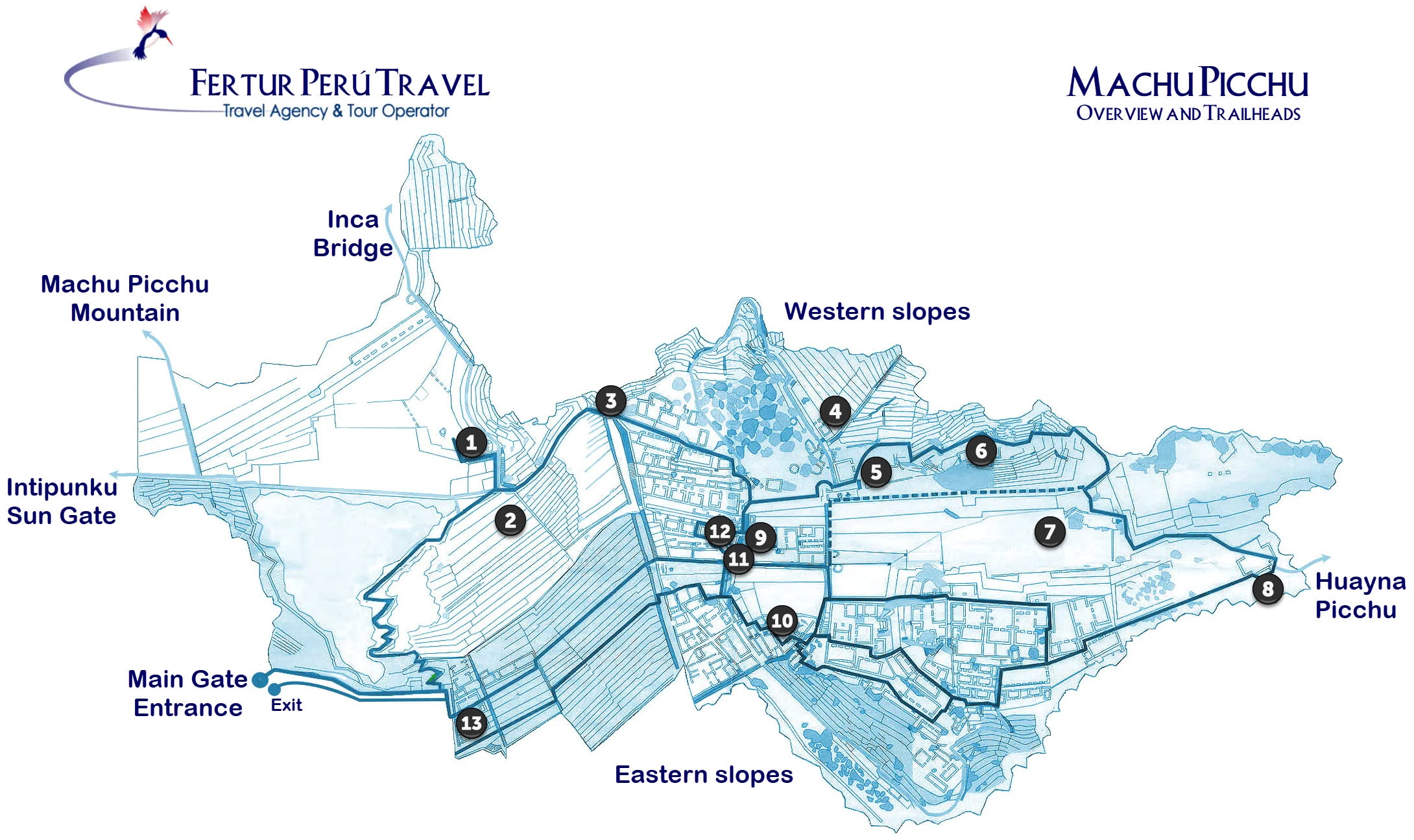

As of June 1, 2024, Machu Picchu introduced new tourist circuits to better organize visitor traffic and preserve the archaeological site. There are now three main circuits, each with multiple sub-routes, totaling 10 different options:

This short route includes the upper terraces near the trail heads to Machu Picchu Mountain and the Sun Gate, followed by the Main Portal, the Granite Quarry, Room of Mirrors and Ceremonial Fountains.

This circuit offers the most panoramic views but does not include access to the lower parts of the site.

This is the longest route, as well as the most complete and popular circuit. It includes the upper terraces (or Qolqas) near the trail heads to Machu Picchu Mountain and Inti punku Sun Gate, followed by the Main Portal, the Granite Quarry area, the Sacred Main Square, the Intihuatana (Temporarily closed to tourists for preservation maintenance), the Sacred Rock, the Room of Mirrors and the Temple of the Condor.

This circuit offers the classic view of Machu Picchu and access to the main archaeological features.

These routes offer the most complete tour of Machu Picchu, including access to main Inca sites like the Temple of the Sun, Main Temple, and Sacred Rock.

Lower terrace short route: Includes the entrance to the Guard House, a walk across the lower platforms (or Qolqas), past the Temple of the Sun, the House of the Inca, the Ceremonial Fountains and the Room of Mirrors.

This circuit focuses on the lower part of Machu Picchu and includes additional hiking options.

All Route 3 options include: Sacred Rock, Twelve-Angle Stone, Eastern Qolqas, Temple of the Condor, Pisonay Plaza

Visitors must choose their preferred route when purchasing tickets. Each circuit has different prices and time slots. Some routes, particularly those including mountain hikes, are only available during the high season (June 1 to October 15).

Below we can see some of the other more important attractions around Machu Picchu and within the nearby mountains, which includes spectacular peaks and ancient Inca ruins. Here at Fertur Travel we see many of these on our custom Cusco Tours, so be sure to check it out now.

The name Huayna Picchu in Quechua means “new mountain.” Rising to 8,763 feet (2,671 meters) above sea level, the summit is girded by Inca buildings, terraces and a shrine on the lower far side, the Temple of the Moon. Reaching the top takes about 50 minutes to an hour and requires a hair-raising, difficult ascent up a narrow trail and through a cave tunnel. Steep granite steps at the top put you literally on the edge of the abyss. The hike sets out from the Sacred Rock at the far north end of the sanctuary. Only 200 visitors are admitted each day, in four shifts: the first from 6:00 to 7:00 a.m., the second from 8:00 to 9:00 a.m., the third from 10:00 to 11:00 a.m., and the fourth from 12 p.m. to 1 p.m. (Note: After completing this route, visitors are not able to re-enter the citadel.)

Its name in Quechua, Huch’uypicchu, means “Little Mountain.” Reaching a height of 8,188 feet (2,496 meters) above sea level, that is exactly what this peak is, situated diminutively alongside the towering Huayna Picchu. Despite its relative stature, the moderate hike to the top offers stunning views of Machu Picchu and the surrounding cloud forest. The 1.2-mile (1.9 kilometer) trek takes about 45 minutes to an hour. From the checkpoint, the hike loops around the lower route above the Eastern terraces, up and over the peak and back out over the upper terraces. The visitor limit per day is 200, spaced over nine shifts throughout the day, with the first schedule from 6:00 to 7:00 a.m. and the last from 2:00 p.m. to 3:00 p.m. (Note: After completing this route, visitors are not able to re-enter the citadel.)

Towering to 10,044 feet (3,061 meters) above sea level, the Quechua name of this higher peak at the southern end of the sanctuary means “old mountain.” The ascent is technically less challenging than Huayna Picchu, but the hike up is longer and no less arduous. Getting to the summit typically requires 90 minutes to two hours, or longer. But at several points along the way, this trek offers unparalleled views of the Inca citadel framed by Huayna Picchu, with the Urubamba River snaking around it in a horseshoe bend. Once on top, you have a 360 degree panoramic vista of the surrounding mountains. The hike begins above the thatched roof Guard House, along a marked stone path that veers off from the trail that leads up to the Inti Punku. The visitor limit per day is 400, again in two shifts: the first from 6:00 to 7:00 a.m. and the second from 8:00 to 9:00 a.m.

As with Huayna Picchu and Machu Picchu Mountain, the trail head begins with a warden’s hut where you must sign in and out. It is a fairly easy, albeit, vertigo-inducing trek. Getting to the bridge takes about 20 to 30 minutes over a winding cloud forest trail. The ever-narrowing path offers some spectacular vistas of the surrounding river valley and mountains. Crossing the Inca Bridge itself is strictly prohibited ever since several years ago when one hiker tried and fell to his death. But it is quite a sight. Four logs are loosely laid over a 20-foot (six-meter) gap in a buttressed section of the trail grafted onto the sheer mountainside. This “drawbridge” provided the Inca controlled access to prevent unwanted guests from slipping in from the Aobamba Valley to the west.

These ruins located at 8,860 feet (2,700 meters) above sea level mark the end of the line for hikers of the Inca Trail, offering them a well-deserved first magnificent view of Huayna Picchu directly ahead and the magnificent stone citadel spread across the saddle ridge below. Day visitors to Machu Picchu can also enjoy this iconic view. Give yourself 45 minutes to an hour to hike up to the Inti Punku from the sanctuary, setting out to the left of the Guard House along the upper terrace.

For years, Inca Trail permits entitled trekkers who arrived through the Inti Punku (Sun Gate) to re-enter the Machu Picchu Sanctuary with access to the upper terraces. This offered another chance to take in the iconic panoramic view of the plaza with Huayna Picchu in the background, and to explore the most important points of interest.

That changed in June 2022 with a new policy, limiting them to the lower terraces and shrines included in Route 3. Hikers of the Classic Inca Trail are no longer entitled to re-enter the sanctuary after exiting. Trekkers of the Short Inca Trail from KM 104 can return the following day.

But for all Inca Trail hikers, in order to return to the upper portion of the sanctuary and tour Routes 1 or 2, they must purchase the additional entry ticket.

The officials at Machu Picchu have signaled that rules of conduct and a list of prohibited items promulgated since 2017 will be more strictly enforced.

Here are the RULES OF CONDUCT and WHAT NOT TO BRING TO MACHU PICCHU!

Items that park guards deem impermissible can be deposited in the cloakroom storage outside the entrance.

To call Machu Picchu a ruins does not do it justice. Covering an area of 37,302 hectares atop the mountain ridge, 250 houses and temples still stand intact after more than 500 years. With its Sacred Plaza at an altitude of 8,261 feet (2,518 meters) above sea level, the stone walls are slanted inward to withstand earthquakes.

As part of their engineering marvel, the Incas constructed an intricate water system of fountains and aqueducts fed by underground springs and made the stone complex self-sufficient with terraced outcroppings for farming. They accomplished all this without the benefit of the wheel nor any form of writing as we understand it. But beyond the inexplicably advanced engineering is the sheer poetic beauty of Machu Picchu.

A haunting reminder of the Inca Empire, the site inspires feelings of cosmic harmony — a bridge between past and present. That is why it was named a World Cultural and Natural Heritage by UNESCO in 1983.

While scholars believe the sanctuary as we know it today was built in the 15th century, a landmark study in 2017 by archaeologist Gori-Tumi Echevarría and former Machu Picchu park director José Bastante, showed that pre-Inca people occupied the mountain for thousands of years.

Echevarría, an expert in the study of “quilcas” — a Quechua term for rock art — documented dozens of petroglyphs and pictograms on the paths leading to Machu Picchu and on shrines within the Citadel. Many of the rock carvings and drawings dated to between 1,000 and 1,400 AD.

It is believed the citadel was built by the Inca emperor Pachacutec starting in about 1440 and was inhabited until the Spanish Conquest in 1532.

Why Machu Picchu was built, and what purpose it served in Inca society, remains an enduring mystery.

Yale anthropology professor Richard Burger and his partner archaeologist Lucy Salazar argue that Machu Picchu’s main function was to provide Pachacutec, his royal entourage and his guests a warm and pleasant “country palace” during the cold Cusco winter months of June, July and August.

Peruvian archaeologist Luis G. Lumbreras first theorized in the 1970s that Machu Picchu is in fact Patallaqta, a “Royal Mausoleum” built — much like the Egyptian pyramids were for the ancient pharaohs — to venerate Pachacutec after his death.

American researcher and explorer Paolo Greer argues that an underground Inca niche with fine coursed stonework excavated in 2009 next to the Torreon (or Temple of the Sun) is, in fact, Pachacutec’s tomb.

In 1987, Spanish historian María del Carmen Martín Rubio discovered 46 lost chapters from Narrative of the Inca, published in 1557 by Chronicler Juan de Betanzos, gathering dust in the private collection of the Fundación Bartolomé March in Palma de Mallorca, Spain.

Betanzos was the official Quechua interpreter for the Conquistadors. His wife was the Inca princess Doña Angelina Yupanque, who had been betrothed in dynastic marriage to her half-brother Atahualpa before Francisco Pizarro had him murdered and took her as his concubine. She married Betanzos after Pizarro’s assassination.

Given his fluency in Quechua, and his wife’s first-hand knowledge of Inca royal lineage, Betanzos is considered one of the most reliable of the Spanish chroniclers.

“After [Pachacutec] was dead,” Betanzos wrote, “he was taken to a town named Patallacta, where he had ordered some houses built in which his body was to be entombed. He was buried by putting his very well dressed body in the earth in a large clay urn.

“Inca Yupanque ordered that a golden image made to resemble him be placed on top of his tomb. And it was to be worshiped in place of him by the people who went there,” the chronicle continues. “He ordered that a statue be made of his fingernails and hair that had been cut in his lifetime. It was made in that town where his body was kept.”

Lumbreras, Greer and Martín Rubio believe the “Patallacta” described — and there are several locations in the Cusco region with that name — is in fact Machu Picchu.

High mountain archaeologist Johan Reinhard suggests that Machu Picchu functioned primarily as a sacred center, where huge landscape alignments of mountain deities and celestial bodies converge.

Reinhard showed how the Intihuatana, the hitching post of the sun, marks a geographic intersection, east-west and north-south, between important mountain deities — Huayna Picchu, or “Young Peak” (North), Wakay Willka, or “Tears of God” (East), Pumasillo, or “Puma’s Claw” (West) and Salkantay, or “Savage Mountain” (South).

According to Inca legend, the Sun was ritually tied to the Intihuatana — the hitching post. At the time of the solstice, when the Sun was farthest from the earth that connection to Machu Picchu acted as a kind of cosmic lasso, preventing the sun from straying any further away on the horizon, ensuring its orderly orbital return.

Looming above Machu Picchu, due North, is the ceremonial mountain peak of Huayna Picchu, while directly south lies Salcantay — one of the most sacred mountain “Apu” deities for the Inca. In May, during the rainy season, the Chacana, or Southern Cross, rises to its highest point in the sky directly above Salcantay. Surrounding the four Crux stars are other star groups and the Yana Phuyu (YA-na FOY-you), a river-like expanse of dark cloud constellations representing the spirits of the animals here on earth.

For the Inca, this corner of the Milky Way was integrally associated with rain and fertility.

On the December solstice, the Sun sets behind the highest snow peak of the distant Pumasillo mountain range to the West. And twice a year, on the solar equinoxes, the Sun comes up behind the snow-covered peak of Wakay Willka (Mount Verónica) and sets behind San Miguel (Mount Vizcachani).

Looking to visit Machu Picchu in the most memorable way possible? Here at Fertur Travel we operate a luxury Machu Picchu and Cusco tour where you will have a highly experienced professional guide show you around the sacred site. As well as riding the legendary Hiram Bingham Train (which includes comfortable seats, refreshments and entertainment), you will also have a memorable city tour around Cusco included.

(Updated July 31, 2024)