Treat yourself to Cusco’s Museum of Pre-Columbian Art

If you are exploring Cusco and the cobble-stoned back streets of the historic San Blas district, consider taking an hour or two, or three, to experience gorgeous pre-Columbian art at the Museo de Arte Precolombino (MAP).

With 398 pieces on permanent loan from the collection of Lima’s Larco Museum, and presented by Larco’s former curator, archaeologist Ulla Holmquist, one might think they’re going to encounter a “Larco Museum-lite.”

But that couldn’t be further from the truth.

“The very name ‘Museum of Pre-Colombian Art’ indicates that the works it contains were selected for their aesthetic value,” wrote renowned Peruvian abstract artist Fernando de Szyszlo soon after the museum first opened in 2003.

The museum was in great part the brainchild of Szyszlo, who passed away in 2017. He believed the primary challenge was how to identify pre-Columbian art “putting the accent on the word art,” rather than “concentrating primarily on the archaeological and historical aspects of our Pre-Hispanic background, which was the usual tendency.”¹

Seeing the art through ancient eyes

Just like at the Larco Museum, the curiatoral texts and audio narrations set the stage with an ancient Andean worldview. Over millennium the inhabitants of successive and overlapping societies — Cupisnique, ChavÃn, Nasca, Paracas, Moche, Chimú, Salinar, Vicús, Virú, Huari, Chancay, Chimu and the Inca — understood their lives in the context of three worlds, or “pachas”:

- Hanan Pacha, or the sky and heavens, “populated by stars, storms, winds, light” and principally represented by depictions of birds, particularly the condor.

- A complement to this world above was a netherworld below, the Uku Pacha. This underground substrate was “dark, wet, the world of the uterus where seeds germinate and take root;” the Pachamama, or mother earth. It was represented with depictions of spiders and serpents.

- And between these two worlds, the Kay Pacha — the here and now — where human daily life took place. “It is the space of the ‘tinkuy’ or meeting point in Quechua. It is the trystlng space where life is generated, because this is where the opposites that need and complement each other meet.” This terrestrial plain is represented by people, as well as animals, including llamas, monkeys and big cats, particularly the puma.

The organization of the museum’s 10 galleries is based less on archaeological theory than on Peru’s diverse geography and the materials that the ancient artists used to create their mythic narratives — stone, wood, shell, silver and gold alloys, and clay.

Besides the written texts accompanying each exhibited piece, the Museum last year started to offer remote audio guides with commentary on the ethnographic and artistic significance of some of the most emblematic works displayed.

For instance, this piece belonging to the Viru cutlure, which evolved along Peru’s northern coast more than 3,000 years ago at the same time the Egyptians were creating hieroglyphics. The narrator remarks on the great detail the artist included in the facial features, toes and toenails.

She also points out the character’s large head, which is not proportional to the body, and speculates that this could point to “a spiritual and intellectual superiority.” (She does not elaborate on another obviously non-proportional part of the character’s anatomy, but does conclude on a timeless tendency, that “art rebounds to the nude.”)

Admission to the museum costs S/.20 for foreign visitors, or a little more than $6 (USD), and an additional S/.20 for the Audio Guide. It is located on the Plaza de las Nazarenas 231 in the Casa Cabrera, believed to originally have been an Inca yachaywasi, or House of Knowledge, where the male children of the Inca noble class received instruction from the empire’s amautas, or teachers.

Following the Spanish founding of Cusco in 1534, the yachaywasi was given to Don Alonso Diaz, son-in-law of Panama’s governor Pedro Anas de Avila, as the city was divvied into plots as spoils for the conquistadors.

In the mansion later became the monastery of Santa Clara to shelter the orphaned daughters of Spaniards killed during years of ruthless infighting between the Conquistadors. Chronicler Diego Esquivel y Navia describes it as a “house for secluded noble maidens, daughters of the first conquerors, who were assisted by the alms paid by city residents, and the City government.”

After the earthquake of 1650, the mansion fell into disrepair. In 1876, the Casa Cabrera was restored and in 1906 it was converted into a school until 1981. That is when Banco Continental acquired the property to restore it and turn it into a cultural center. Originally it was used as an art gallery and auditorium, until 2002 when BBVA Continental created the present MAP.

Pre-Columbian Art in the Post-Columbian World

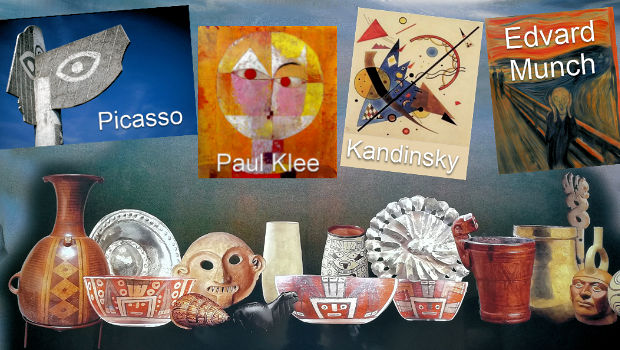

The museum goes out of its way to point out the impact the Pre-Columbian art has had on great artists like Paul Gauguin, Edvard Munch, Henry Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Wassili Kandinsky, Constantin Brancusi, Paul Klee, Henry Moore, and Fernando de Szyszlo, among others.

The grand stairwell of the museum is lined with quotes from famous artists and social scientists about the influence of pre-Columbian art on modern art.

Our sympathy and our spiritual relationship lie with the primitives, because like us these artists seek to express in their work only inner truths, renouncing, therefore, all that is distracting in surrounding form.

Wassili Kandinsky (1866 – 1944)

The day is surely not far away when collections from distant parts of the world will leave ethnographic museums to take up their rightful place in art museums.

Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908 – 2009)

In all my life I have not seen objects which have touched my heart in this way”¦ because I saw, among these things, marvelous works of art and I was astonished by the subtle wit of these men from such faraway lands.

Alberto Durera (1471-1528)

It is during this century, thanks to the transformations undergone by art, and therefore by art criticism, that the value and importance which is its due has been attributed to so-called primitive art.

Fernando de Szyszlo (1925—2017)

¹ Exaltation of Beauty: The new Museum of Pre-Colombian Art opened its doors in Cuzco, By Fernando de Szyszlo, Chasqui Peruvian Mail, Cultural Bulletin of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 3 (2004), pp.6-7

Lima voted TOP property in MONOPOLY HERE & NOW: World Edition

Lima voted TOP property in MONOPOLY HERE & NOW: World Edition  How To Celebrate New Years Eve in Peru for guaranteed great time?

How To Celebrate New Years Eve in Peru for guaranteed great time?  Manu Family Vacation and an Actor’s Tribute to Roger Corman

Manu Family Vacation and an Actor’s Tribute to Roger Corman  Peru 2016 holiday calendar – Download

Peru 2016 holiday calendar – Download  Spooky Pre-Halloween Sighting By Security Patrol in Peru

Spooky Pre-Halloween Sighting By Security Patrol in Peru  Paddington Bear’s Peru Tour includes COP20 appearance

Paddington Bear’s Peru Tour includes COP20 appearance  Joss Stone chooses ancient Peru pyramid for 2015 performance

Joss Stone chooses ancient Peru pyramid for 2015 performance  Vargas Llosa and other celebrity sightings at Machu Picchu so far in 2017

Vargas Llosa and other celebrity sightings at Machu Picchu so far in 2017