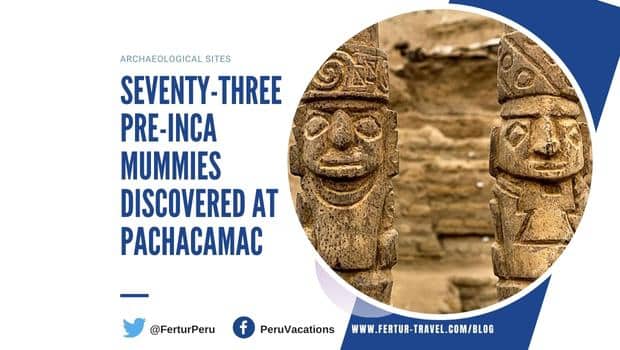

Important Pre-Inca Mummies and Wari Staff Idols Discovered at Pachacamac

Archaeologists just unearthed 73 pre-Inca mummies at Pachacamac, with wood and ceramic “false head” masks, along with two very important Wari idol staffs.

The detective work that went into the discovery of the intact funerary bundles and archaeological relics is as fascinating as their scientific significance.

The bundled, also known as fardos, date back to the Wari culture, which flourished between 800 and 1100. During this period, the Wari Empire expanded its influence throughout western South America.

The newly discovered burials at Pachacámac provide a rare and captivating glimpse into the customs and rituals of this ancient civilization.

Overview of Wari Archaeological Find at Pachacamac

Elaborate Burial Practices

Both male and female bodies were found adorned with “false heads,” which resemble human faces, meticulously crafted to honor and preserve the memory of the deceased.

According to Krzysztof Makowski, the leader of the archaeological project, these false heads served as a symbolic link between the living and the dead. They were believed to ensure a dignified afterlife for the deceased and facilitate communication between the mortal and the spiritual realms.

The use of such masks in burial rituals was a common practice among the Wari culture, highlighting their deep reverence for their ancestors and the importance they placed on maintaining a connection with them even after death.

The significance of the discovery was explained on the ArcheowieÅ›ci archaeology web site, published by the Faculty of Archaeology of the University of Warsaw, Makowski’s alma mater.

For Krzysztof Makowski, a Polish archaeologist who immigrated to Peru in 1983, and his team, this discovery at Pachacámac marks one of the most significant unearthed there for a couple of decades.

Excavation conducted by Peter Eeckhout of the Free University of Brussels in 2005 uncovered 69 tombs and funerary bundles at Pachacámac. Some contained entire families interred together. Others held the carefully preserved remains of pilgrims who had likely journeyed to the Pachacámac oracle seeking cures for diseases like syphilis, tuberculosis, and even cancer.

Archaeology Detectives Find the Mummies that Looters Missed

For centuries, Pachacámac was the scene of plunder. First came the gold-hungry Spanish Conquistadors. And then there was the Spanish Colonial era’s Extirpation in Peru, when the Catholic Church tried, and failed, to eradicate traditional native religious practices.

That was followed by hundreds of years of “huaquero” grave robbers desecrating the burial sites in search of relics to sell.

Professor Makowski and his colleagues Cynthia Vargas, Doménico Villavicencio, and Ana Fernández intentionally focused their research on an area where a high wall from Inca and colonial times had collapsed. They theorized that the fallen adobe bricks would have made it challenging for grave robbers to access the site.

Their hypothesis proved right — the adobe debris did deter looters and preserved the integrity of the graves. By excavating this previously-inaccessible spot, the researchers were able to uncover the well-preserved burials that had avoided disturbance since the wall initially crumbled long ago.

The fortuitous collapse that once destroyed the wall ultimately helped protect the ancestral remains buried in its shadow for future discovery.

Colorful Ceramics and Artifacts

Alongside the burials, archaeologists also discovered a treasure trove of ceramics within the grave sites, dating to approximately 900-1000 AD, or about 1,000 to 1,100 years ago when the Wari Empire controlled Pachacámac.

Influence of the Tiwanaku Kingdom

According to Makowski, the discovery reveals not only the practices of the Wari culture but also intriguing connections with other ancient civilizations.

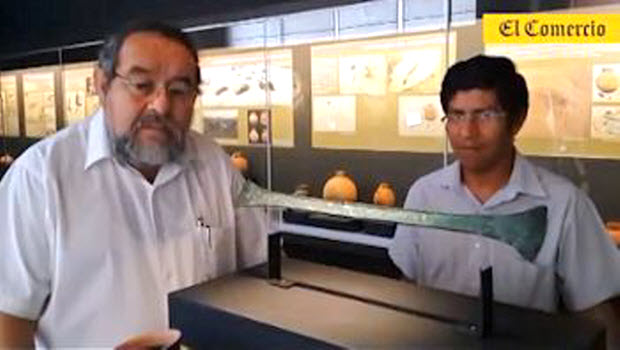

The two wooden staffs discovered in the remains of a nearby settlement provide evidence of contact between the people of Pachacámac and the Tiwanaku kingdom, Makowski wrote. Specifically, the carvings depict dignitaries wearing headgear typical of Tiwanaku, which spanned across modern-day Peru, Bolivia, and Chile.

“The style of these staff is comparable to the famous cult image known as the ”˜idol of Pachacámac’,” from Inca times. However, the earlier Tiwanaku-type headgear on the Wari-era idols is important evidence of interaction between the two cultures.

This discovery highlights the extensive networks and cultural exchanges that existed between different civilizations in ancient South America.

Successive Empires Controlled Pachacámac: Wari, Inca & Spanish

Throughout its history, Pachacámac has experienced significant transformations.

A sprawling ceremonial center of 18 mud-brick pyramids with ramps and plazas, Pachacámac was one of the most important pre-Hispanic cities of the Andean coast.

Today, the pilgrimage to Pachacámac is made by tourists, who flock to the vast archaeological zone located in the fertile Lurin Valley, 20 miles south of Peru’s capital, Lima.

But it was first ruled by the Ychsma culture from 900 A.D. Research indicates that during the time of the Wari Empire, the settlement was relatively modest. However, with the rise of the Inca Empire in the 15th century, Pachacámac became a major religious center and grew in importance.

When the Inca took control of Pachacámac, they gained control of the venerated spiritual center of the Pacific coast — a vitally important center of strategic power from which to advance their empire.

Less than a century later, in 1533, contemplating a similar tactical takeover, Spanish Conquistador Francisco Pizarro set his sights on the temple city. He sent his brother, Hernando, who plundered the site and desecrated the idol that served as the oracle.

These historical events are related wonderfully in Sabine MacCormack’s Gods, Demons, and Idols in the Andes, published in the Journal of the History of Ideas, [Volume 67].

Gold from the temples had already been hastily collected for transport to the northern Andean city of Cajamarca to pay the ransom for the captured Inca Atahualpa. Upon receiving the treasure, Pizarro had Atahualpa executed anyway by garroting.

Miguel de Estete, one of the Spaniards present, later described how his party of conquistadors pushed their way past the temple priests through a door “adorned with coral and turquoise, crystals and other things” to enter a small, dark room.

Spanish Conquistadors Encounter the Oracle Idol Staff

There, illuminated by candlelight, the Spaniards found the oracle: “A filthy wooden pole fixed in the ground with the figure of a man at its top, poorly carved and poorly shaped,” Estete wrote. “Small gold and silver offerings” were scattered around it.

“Seeing how vile and despicable the idol was, we went outside to ask why they cared about so mean and ungainly a thing,” he wrote. “But they, astounded at our daring, defended the honor of their god and said that he was Pachacámac, the Maker of the World who healed their infirmities.

“According to what we were able to learn, the devil appeared to those priests in that hovel and spoke with them,” Estete continued. “They entered there with the petitions and offerings of the people who came in pilgrimage, because they came from the entire kingdom of Atahuallpa, just as Moors and Turks go to the house in Mecca.”

The Spanish soldiers gathered together the leaders to “enlighten” them.

“In the presence of all, the hovel was opened and torn down,” Estete recounted, “and with much solemnity a tall cross was raised over the seat which for so long the devil had claimed as his own.”

Another conquistador, Francisco de Jerez, wrote that Captain Hernando Pizarro “broke the idol in the sight of everyone,” offered them instructions to follow the Catholic faith, and “gave them as armor to defend themselves against the devil the sign of the cross.”

In the ensuing years, the Spanish tried in vain to destroy any vestige of such idols venerated by native civilizations like the Wari and Inca.

Five hundred years later, Prof. Makowski and his team uncovered two oracle staffs that the Spanish and the looters missed.

[Originally published November 29, 2023]

Bibliography:

[Miguel de Estete – Relación del descubrimiento del Perú (1534)]

[Francisco de Jerez. – Verdadera relación de la Conquista del Perú (1534)]

Design of new visitor complex entrance chosen for Machu Picchu

Design of new visitor complex entrance chosen for Machu Picchu  Regulating the back door entrance to Machu Picchu

Regulating the back door entrance to Machu Picchu  Free exhibit of ancient artifacts from El Chorro tombs

Free exhibit of ancient artifacts from El Chorro tombs  Mandatory tour guides and fixed routes coming soon for Machu Picchu

Mandatory tour guides and fixed routes coming soon for Machu Picchu  Book your Cusco trip featuring the Inti Raymi Festival

Book your Cusco trip featuring the Inti Raymi Festival  How to pronounce the name of that awesome ruins above Cusco

How to pronounce the name of that awesome ruins above Cusco  Seven reasons to visit the temple fortress of Kuelap on your vacation to Peru

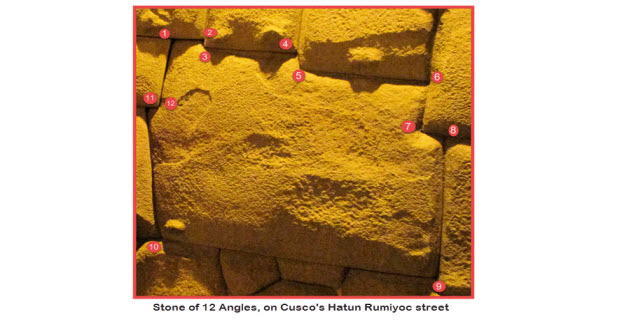

Seven reasons to visit the temple fortress of Kuelap on your vacation to Peru  Famous 12 angle Inca stone topped but not overshadowed by 13 angle stone

Famous 12 angle Inca stone topped but not overshadowed by 13 angle stone