Unearthing the Chinkana: Peru’s Search for the Inca’s Lost Tunnels

For hundreds of years there were tales of Cusco’s hidden tunnels — labyrinth stone passageways connecting sacred Inca sites. For many, the tales are mere folklore. But a pair of Peruvian archaeologists appear on the verge of proving the stories true.

At a remote rocky outcrop within the Sacsayhuamán Archaeological Park, Dr. Jorge Calero and Dr. Mildred Fernández are leading a historic excavation known as the Chinkana Project.

The archaeologists announced the definitive discovery of tunnels beneath the Sacsayhuamán esplanade in January using sound prospecting and ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys

Excavations started last month. After 45 days, the team believes it has located the true entrance to an underground Inca thoroughfare — one that runs nearly 1,750 meters (about 1.1 miles), linking Sacsayhuamán to the Qorikancha, the most important temple of the Inca Empire.

“This isn’t a fantasy,” Dr. Calero tells Agencia Andina correspondent Percy Hurtado. “We have both historical documentation and scientific evidence. What we’re uncovering is real.”

Decoding a Legend

The Chinkana, often translated as “labyrinth” or “place where one gets lost,” has been mentioned in Andean chronicles since the 16th century. Spanish priest Martín de Murúa wrote that Emperor Huayna Capac built a temple shaped like a serpent’s head — a site associated with dark mystery and celestial observation.

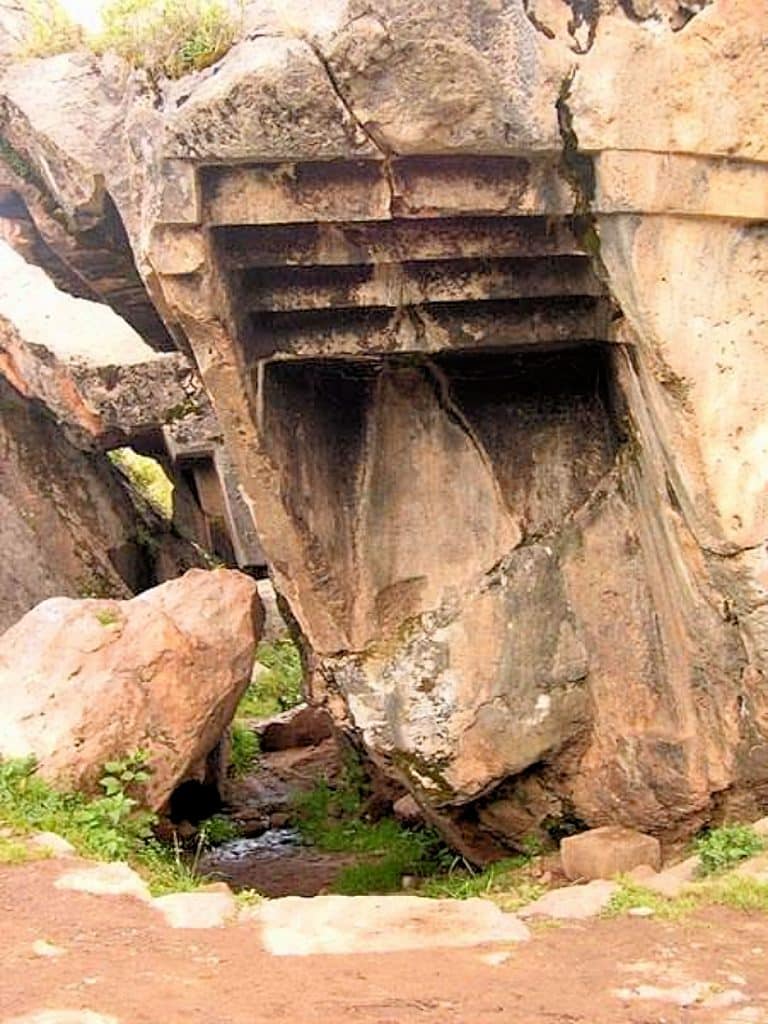

Standing before a cavity in the Chinkana Chica within Sacsayhuamán, Calero points to a weathered stone bearing a distinct resemblance to a serpent’s head. “This matches Murúa’s description,” he said. “We believe this is the very structure that once crowned the temple.”

According to the archaeologist, the original entrance to the Chinkana was sealed with explosives in the 19th century, likely by General San Román in 1841. That account is supported by an 1867 travelogue written by American explorer Ephraim George Squier:

“The interior and remoter ramifications cannot now be followed, since General San Roman, when Prefect of Cuzco, had some of the passages walled up, in consequence of the recurrence of accidents — the last accident happening to three boys, who were lost and starved to death in the recesses of the Chingana.”

Beyond the Myths

Tales abound of wayward explorers and treasure hunters entering the mysterious tunnels from the entrance at Sacsayhuaman, most never to emerge again.

“One man, indeed, is said to have found his way underground to the Sun Temple, and when he emerged, to have had two golden bars in his hand,” William Montgomery McGovern contended in his 1927 book Jungle Paths and Inca Ruins. “But his mind had been affected by days of blind wandering in the subterranean caves, and he died almost immediately afterwards.”

The main entrance to the tunnel system was believed to be the so-called “Chinkana Grande,” a cavernous area popular with curious youths and urban adventurers. Some even boast of having emerged near the cathedral. But Calero is adamant: “That site, known as the Tired Stone, is not the Chinkana. The real entrance is here, near the Rodadero.”

Previous attempts to locate the tunnels failed, often due to misreadings of colonial documents and insufficient archaeological rigor. Calero specifically cited the unsuccessful excavations 25 years ago by the Spanish explorer Anselm Pi Rambla. Those efforts failed, Calero said, because investigators “haven’t properly analyzed the chronicle documents and traveler documents.”

A Sacred Alignment

The Chinkana Project excavation site is more than a suspected tunnel. The structure surrounding the presumed entrance was designed in relation to surrounding huacas, or sacred sites, according to Inca cosmology and sacred duality of the universe.

“This is a feminine temple,” Calero explained. “Built by Huayna Capac in honor of his wife, who represented Pachamama — the earth mother. The Inca, as son of the sun, was her divine counterpart. Their union mirrored the harmony between sun and earth.”

The site’s design and orientation reinforce its ritual purpose. Each segment of the temple aligns with a cardinal solar event. The eastern face is illuminated by the sun on the equinoxes, March 21 and September 21. The southern wall aligns with the June solstice; the northern side, with the December solstice. These precise alignments, Calero noted, suggest the structure also served as a stellar observatory, allowing its builders to track key constellations such as Corona Borealis — known to the Inca as Llamacancha—and Lyra, or Orcochillay.

“This was a place of both astronomy and ceremony,” he said. “A sacred space built to reflect the cosmos and the divine feminine.”

A Network Beneath the Puma

Using ground-penetrating radar (GPR) donated by the Swiss firm Proceq, Fernández and her team have detected anomalies — voids spanning from approximately 60 centimeters to 2.5 meters in depth. These cavities may represent collapsed or sealed segments of the Chinkana. The data suggests multiple branches, some passing beneath the Plaza de Armas and extending toward the Archbishop’s Palace.

The team has identified nine primary excavation points along the suspected tunnel route, though some locations have proven inaccessible due to stone obstructions.

“We estimate up to 8 kilometers [nearly 5 miles] of underground passages beneath Cusco,” Fernández said. “It’s a complex, interconnected system — exactly as Garcilaso de la Vega described, where you needed a rope to avoid getting lost.”

Anecdotal evidence supports their findings. At the Las Mercedes school, where Fernández’s mother once studied, children used to sneak into a tunnel system. During construction near the San Cristóbal Temple, two workers fell into a cavity now believed to be part of the Chinkana. The entrance was hastily sealed with concrete.

Risks Underground

Entering the tunnels poses hazards. Inside, the air is thick with gases and mold, including Aspergillus. Calero recently contracted a throat infection from Aspergillus fungus after briefly removing his protective mask during current excavation work. Any rush to access the passages, he warned, could destroy fragile organic materials preserved for centuries in the sealed environment.

“This isn’t just about discovery,” he said. “It’s about preservation. We owe it to the people of Peru to do this right.”

Controversy Above Ground

The project has not been without conflict. Recently, Calero’s team complained to the Ministry of Culture that unauthorized foreign researchers — two Polish citizens and one Peruvian — using a GPR device near the excavation zone without permits or Peruvian archaeologists present.

“It’s unethical and illegal,” Calero said. “This is a restricted zone, and our team holds the exclusive authorization.”

Both archaeologists have appealed to Peru’s Ministry of Culture and Congress to protect the site and their yearlong permit. They fear a rush of opportunistic researchers may try to capitalize on their progress.

“We announced our project in January,” Fernández added. “The excavation began approximately 45 days ago. Now others want to interfere. This investigation must be respected.”

A Matter of Pride

For Calero and Fernández, this is more than a scientific endeavor. It’s about reclaiming Peru’s narrative.

“Too often we hear that foreign scholars discover our past,” Fernández said. “But we are Indigenous Peruvians. We’re leading this work. We’re telling our story.”

As they prepare to open the sealed passage—within weeks to months, though archaeological timelines are inherently unpredictable—expectations are high. The implications are vast: a new understanding of Inca infrastructure, ritual architecture, astronomical alignments, and sacred geometry. Perhaps most importantly, it offers Peruvians a deeper connection to their own history—buried just beneath their feet.

Book your Cusco trip featuring the Inti Raymi Festival

Book your Cusco trip featuring the Inti Raymi Festival  The virtual reality of Inca architecture: Sacsayhuaman

The virtual reality of Inca architecture: Sacsayhuaman  Regulating the back door entrance to Machu Picchu

Regulating the back door entrance to Machu Picchu  Free exhibit of ancient artifacts from El Chorro tombs

Free exhibit of ancient artifacts from El Chorro tombs  Mandatory tour guides and fixed routes coming soon for Machu Picchu

Mandatory tour guides and fixed routes coming soon for Machu Picchu  See yourself in the star mirrors of Machu Picchu

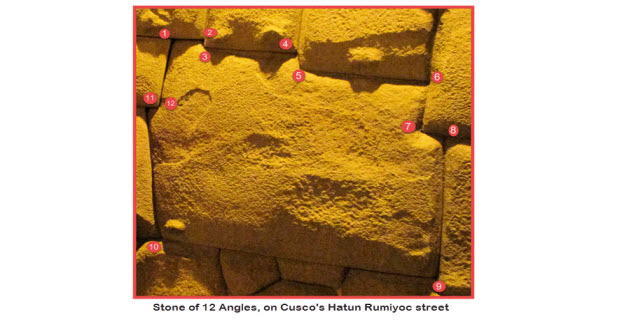

See yourself in the star mirrors of Machu Picchu  Famous 12 angle Inca stone topped but not overshadowed by 13 angle stone

Famous 12 angle Inca stone topped but not overshadowed by 13 angle stone  How to pronounce the name of that awesome ruins above Cusco

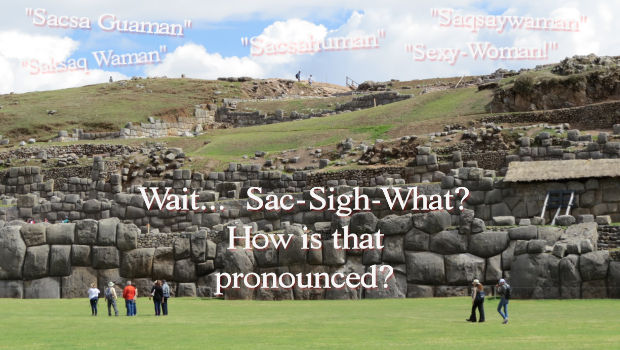

How to pronounce the name of that awesome ruins above Cusco

Instead of defaming other archeologists with permits, Calero should release a peer-reviewed article. Or at the very least, present one photograph of a tunnel.

Anseml Pi Rambla should at least get a mention here,